2025

NorwayYou don´t have cancer until the pathologist says so!

Patologene er ekspert på diagnoser, stiller kreftdiagnosene og mange andre pasientdiagnoser!

Kunnskap for din riktige diagnose, behandling og prognose!

Faglig kompetanse- din sikkerhet som pasient!

Patologi med focus på deg og pasientene!

Patologi før behandling!

Without pathology, there is no medicine!

Patologi/ Pathology er meget viktig for diagnose, behandling og prognose. patologiworld.com

Mye om patologi Vev Celler Mikroskop senter med fakta – Pathology collection and center with correct facts from Oslo Norway News – Funn – Diagnose – Prognose – Forskning – Vitenskap – Nyheter – Kreft – Bryst – best nice website – Pathology excellent center. Immunhistologi Genetikk.

Copyright © SkyPat 1996 Birger Fr. Motzfeldt Laane

Hvis du vil ha mere informasjon så gå til MENU på siden og til linkene nedenfor!

NYE INNLEGG LIGGER UNDER BLOGG I MENYEN!

Reklamene som du ser på sidene kan bare dekke en liten del av driftskostnadene,

men inntekter fra reklamene kommer bare inn hvis du er så snill å klikke på disse!!!!

For deg skjer ingenting!

Da kommer det inn til den tekniske side et par kroner til litt dekning av utgiftene. Tusen takk!

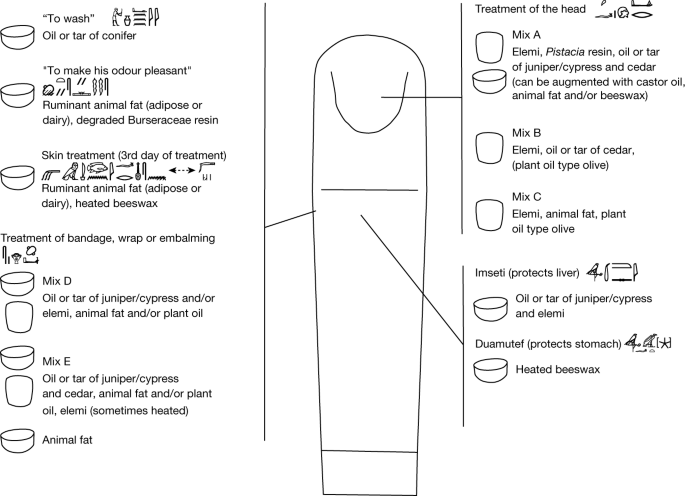

Prof Dr Morten Laane (1940-2024) from Norway identifing Borrelia with darkfield microscopy. Borreliosis facts

Nivået på kritikken mot oss framstår som at enkelte er mer opptatte av å dele ut karakteristikker enn å fokusere på pasientenes beste.

Hentet fra Dagbladets artikkel publisert den 27.mars 2015

av Carl-Morten M. Laane

Professor emeritus, molekylærbiologi

I en artikkel kalt «De ga Lars Monsen diagnosene Borrelia og babesiose» på db.no den 6. mars, blir undertegnede og kollega Ivar Mysterud gjenstand for kritikk.

I artikkelen framkommer en rekke påstander og feil.

Babesia og Borrelia er for det første navn på to ulike mikroorganismer og IKKE sykdommer. Vår forskning har hatt som mål å identifisere hvorvidt disse mikroorganismene er til stede i blod, ikke å gi diagnoser.

Artikkelen slår videre fast at «Mikroskopi ikke er egnet for å påvise Borrelia og Babesia». Dette er feil. Uten mikroskop hadde disse etter alt å dømme IKKE vært oppdaget. Tannspiroketer, av samme type mikroorganisme som gir Borreliose, ble oppdaget i 1695. Infeksjonsmedisinen endret seg fra kvakksalveri til reell vitenskap rett etter 1871 da Zeissfabrikken i samarbeid med Otto Schott og Ernst Abbé i Tyskland utviklet optisk perfekte mikroskopobjektiver. Ørsmå bakterier kunne ses skarpt for første gang. Dette førte raskt til oppdagelsen av en lang rekke mikroorganismer som årsak til smittsomme sykdommer.

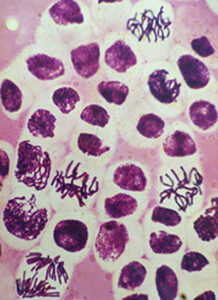

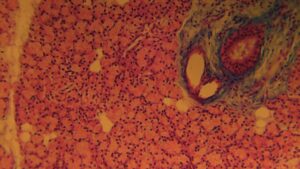

Metoden for Babesia er en forbedring av standard metode for påvisning av malariaparasitten. Babesia omfatter en artsgruppe som er svært nær beslektet. Den forbedrete metoden gir kraftigere farging, det vil si at parasitten framkommer sterkere og klarere. I vår siste artikkel i tidsskriftet Biolog viste vi dette med enkle, effektive liknende metoder.

Bakteriologien er utviklet bl.a. av Cohn (1875), Koch (1876), Lister (1878), Pasteur (1880), Koch (1881), Mechnikoff (1882), Koch (1884), Pasteur (1885), Beijerinck (1889) og utallige etterfølgere. Mikroskopien utvikles stadig etter 320 års omfattende studier.

Det ser ut som at Folkehelseinstituttet mener at smitte representerer en sykdom. Det er i så fall feil. Alle utsettes for smittestoffer. Hvorvidt det utvikles sykdom avhenger av immunsystemet.

Av medieomtale, publikasjoner og avtalen oss imellom framgår det at jeg og kollega Mysterud er ansett som likeverdig faglig samarbeidspartner. Dette harmonerer dårlig med «pensjonisthobby»-inntrykket i artikkelen.

Nivået på kritikken fra den tidligere smittevernlegen i saken framstår som at enkelte er mer opptatte av å dele ut karakteristikker enn å fokusere på pasientenes beste. I stedet for å se på vår forskning som et verdifullt bidrag for å forbedre molekylære laboratorieteknikker, avvises mikroskopi som viktig førstehåndskunnskap. Det er i beste fall historieløst.

Krybbedødmysteriet-

NRK. Podkast

https://radio.nrk.no/podkast/yeblikket/l_b70a9d16-3b3e-4abd-8a9d-163b3e2abd07

Digital patologi – Siemens Healthineers Norge

https://www.siemens-healthineers.com/no/digital-health-solutions/digital-patologi

Digital patologi – Siemens Healthineers Norge

AI-klar plattform med fleksibel, robust og skalerbar arkitektur. Bygget for å støtte patologens arbeidsflyt og fulldigital diagnostikk.

https://www.siemens-healthineers.com/no/digital-health-solutions/digital-patologi

Multi-year agreement will power 100% digitization of Uppsala’s clinical workflow and future AI integrations

UPPSALA, Sweden & PHILADELPHIA, PA – February 3, 2022 – Proscia®, the leader in digital and computational pathology solutions, and Uppsala University Hospital, Sweden’s oldest university hospital, today announced a multi-year agreement to fully digitize the region’s pathology workflows. The division of Laboratory Medicine at Uppsala University Hospital has selected Proscia’s Concentriq® Dx digital pathology solution for full-scale digitization and future deployment of AI applications in routine operations at scale, empowering the region’s pathologists to drive increased quality and productivity gains and unlock hidden insights to better inform patient care.

The widespread adoption of digital pathology is enabling laboratories to push past the limitations of traditional pathology practices. As laboratories adopt digital pathology, they must leverage a complex ecosystem of hardware and software solutions that each play a key role in the pathologist’s workflow. These laboratories are now recognizing that practicing digital pathology at scale requires an open approach grounded on broad interoperability to centralize critical data and routine operations. Uppsala University Hospital selected Proscia for its novel ability to empower the modern laboratory with its enterprise-class platform that addresses current and future requirements, strategically improves decision-making, drives new discoveries, and accelerates medical breakthroughs.

Proscia’s technology will drive Uppsala’s modernization efforts and its goal of becoming completely digitized. The technology will support the region in achieving widespread, seamless integration with leading scanners, laboratory information systems, and image analysis applications. Proscia’s Concentriq will equip the clinical pathology lab at University Hospital with streamlined and intuitive workflows that ensure secure, remote access to cases and images.

“Uppsala University Hospital is propelled by its vision to become the leading university hospital creating the most value for its patients,” said professor emerita Irina Alafuzoff, Senior Consultant in Neuropathology, part of the laboratory medicine division at Uppsala University Hospital. “As we strive to advance our region to a digitized future, our working group including several pathologists, biomedical analysts, and representatives with IT expertise, evaluated multiple enterprise solutions and selected Proscia for its highly nimble and knowledgeable approach to computational pathology. We are confident that Concentriq’s scalable and open platform will drive us to the forefront of innovation as we work to empower the future of our laboratories.”

Proscia’s Concentriq digital pathology platform is a robust, end-to-end solution for connecting distributed teams, data, and applications across the global enterprise. The flagship software is used by leading laboratories and health systems, as well as 10 of the top 20 pharmaceutical companies. With Concentriq, laboratories can tap into the interoperability and scalability required to achieve streamlined, reliable operations for pathologists and enhanced outcomes for patients.

“We are thrilled about the opportunity to invest in the Nordic region’s digitization efforts and honored to have been selected as Uppsala’s solution to achieve full digitization by 2024 and elevate the region as a center of excellence,” said David West, CEO, Proscia. “We look forward to helping Uppsala shift its pathology standard of care to a data-driven discipline and optimize their laboratory operations to drive rapid innovation within the field of pathology.”

About Region Uppsala

Region Uppsala has about 380,000 residents, of which about 227,000 reside in Uppsala municipality. The most important task for Region Uppsala is to provide the people in the county with good health and medical care: from highly specialized healthcare to cultural activities, from the large university hospital in Uppsala to the small healthcare centre in Almunge.

About Proscia

Proscia is a software company that is accelerating pathology’s digital transformation to change the way we understand diseases like cancer. Its Concentriq digital pathology platform and powerful AI applications are advancing the 150-year-old standard of research and diagnosis toward a data-driven discipline, unlocking new insights that accelerate discovery, improve patient outcomes, and fulfill the promise of precision care. Leading diagnostic laboratories and over 10 of the top 20 pharmaceutical companies rely on Proscia’s software each day.

Hentet fra ChatGPT (ChatGPT (Chat Generative Pre-trained Transformer) is a chatbot launched by OpenAI ):

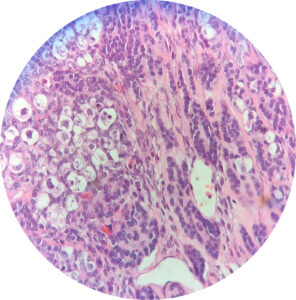

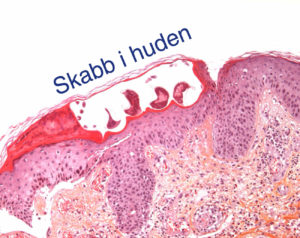

Hvorfor bruker man histopathology

Histopathology er en viktig teknikk i diagnostikk og behandling av sykdom. Det brukes til å undersøke vevprøver fra en biopsi eller et vevsstykke som er fjernet under en kirurgisk operasjon for å identifisere sykdommer eller forstyrrelser i kroppen.

Fordelene med å bruke histopathology inkluderer:

- Diagnostisering av sykdommer: Histopathology hjelper leger med å identifisere ulike sykdommer ved å undersøke vevstrukturer og celler.

- Behandlingsplanlegging: Informasjonen som er innsamlet gjennom histopathology kan hjelpe leger med å utarbeide en mer nøyaktig behandlingsplan for pasienten.

- Evaluering av effektiviteten av behandling: Histopathology kan brukes til å vurdere effekten av behandling ved å sammenligne vevprøver før og etter behandling.

- Forskning og utvikling: Histopathology bidrar også til forskning og utvikling av nye behandlinger ved å gi en bedre forståelse av sykdomsprosessen og vevsskade.

Alt i alt er histopathology en nødvendig teknikk for å støtte medisinsk diagnose og behandling, og det bidrar til en mer nøyaktig og effektiv behandling av sykdommer.

Er det negative sider ved screening av livmorhalskreft?

Ja, det er noen negative sider ved screening for livmorhalskreft, inkludert:

- Feilpositive resultater: Screening kan resultere i feilpositive resultater, noe som kan føre til unødvendige bekymringer og ytterligere undersøkelser.

- Overdiagnostikk: Screening kan også føre til overdiagnostikk, hvor sykdommer oppdages som aldri ville ha blitt en helseproblemer for den enkelte personen.

- Overbehandling: Overdiagnostikk kan også føre til overbehandling, hvor folk behandles for sykdommer som ikke nødvendigvis trenger behandling.

- Risiko for skade: Noen screeningstester, for eksempel kolposkopi, kan resultere i mindre skader på livmorhalsen.

- Kostnad: Screening for livmorhalskreft kan være dyrt, spesielt for folk som ikke har god helseforsikring.

Alt i alt er det viktig å veie opp fordelene og ulempene ved screening for livmorhalskreft, og å diskutere mulige risikoer og fordeler med legen din for å bestemme om screening er riktig for deg.

Er det negative sider ved screening av mammakreft og angi forfattere med dette synet, og også med https?

Ja, det er noen negative sider ved screening for brystkreft, inkludert:

- Feilpositive resultater: Screening kan resultere i feilpositive resultater, noe som kan føre til unødvendige bekymringer og ytterligere undersøkelser.

- Overdiagnostikk: Screening kan også føre til overdiagnostikk, hvor sykdommer oppdages som aldri ville ha blitt en helseproblemer for den enkelte personen.

- Overbehandling: Overdiagnostikk kan også føre til overbehandling, hvor folk behandles for sykdommer som ikke nødvendigvis trenger behandling.

- Risiko for skade: Noen screeningstester, for eksempel mammografi, kan resultere i mindre skader på brystvevet.

- Kostnad: Screening for brystkreft kan være dyrt, spesielt for folk som ikke har god helseforsikring.

Flere forfattere har skrevet om negative sider ved screening for brystkreft, inkludert Dr. H. Gilbert Welch, en epidemiolog og forfatter av bøkene “Overdiagnosed: Making People Sick in the Pursuit of Health” og “Less Medicine, More Health”.

Det er også flere artikler og rapporterer om negative sider ved screening for brystkreft som kan finnes via en enkel online søk. For eksempel, denne artikkelen fra “The Guardian”: https://www.theguardian.com/science/sifting-the-evidence/2015/oct/15/breast-cancer-screening-overdiagnosis-overtreatment.

Regenerate response

Hentet fra NRK:

Skal lagre pasientdata i amerikansk sky

Pasientdataene til Helse Sørøst – altså data fra halvparten av alle nordmenn – skal bli lagret i en amerikanskeid sky-løsning.

EU-reglene sier at opplysningene må beskyttes slik at de ikke kan utleveres til land utenfor Europa.

Datatilsynet håper en avtale mellom EU og USA er på plass i løpet av høsten, men det er høyst uklart om de klarer å få det til.

Fra Document:

Helse Sør-Øst vil sende pasientdata til skyløsning i USA

Egne bemerkninger:

Før hadde helsevesenet/ alle involverte/ ansatte i Norge taushetsplikt angående pasientdata/ pasientjournal.

Mulig på grunn av datainføringer, økonomiske faktorer og mulig mangel på kompliserte dataprogrammer/ lagringssteder og dataeksperter, er det etter at man gikk over fra “mere sikre papirjournaler” eller datalagring mere lokalt, kommet en rekke opplegg/ gjøremål fra helsevesenet som utvanner de taushetsbelagte pasientopplysningene, særlig innen helse.

Dette kan gjelde datahjelp med sendte helseopplysninger til andre land (f. eks. Litauen) og røntgendiagnostisering til billigere utenlandske aktører. Dette er ille for for oss alle (alle blir vi pasienter) og er eller burde være ulovlig. Det ser ut til at dette ble stoppet. NAV kan pussig nok innhente pasientopplysninge som de mener de trenger.

Nå er det mye verre hvis dette nye går igjennom!!!!

I det alt på Internett mer eller mindre “flyter omkring” selv med de beste sikkerhetsopplegg, vil det nok i fremtiden være en rekke “sikkerhetshull” i et slikt system. Det kan f.eks. være interessant for andre makter, myndigheter og utenlandske eller norske forskere/ hjelpere.

Hvem er ansvarlig og hvem har ansvaret nå og i fremtiden når systemet ligger utenfor landet? Hva med det utenlandske “private” firma som eventuelt får nye eiere/ bli kjøpt opp av andre/ andre land eller går konkurs? Det vil bli en oppsmuldring av ansvar, noe man ofte har sett i andre saker!

I det de som sitter i Helse Sørøst er valgt inn, vil ansvaret i fremtiden nærmest forsvinne.

Datatilsynet og Helsedirektoratet må stoppe forslaget og lage fremtidige opplegg for datasikkerhet/ taushetsbelagte pasienthelseopplysninger innen privat og offentlig helsevesen, og ikke la en slik offentlig/ halvprivat (se Brønnøysundregisteret) som Helse SørØst, få gjøre mere nærmest som de vil! (De tenker oftest og mest på økonomi!)

Reklamene som du ser på sidene kan bare dekke en liten del av driftskostnadene, men bare hvis du er så snill å klikke på annonser!!! For deg skjer ingenting. Da kommer det inn til den tekniske side et par kroner til litt dekning av utgiftene. Tusen takk!

Free/ gratis pdf- download av bøker, bl.a. innen patologi fra: https://www.pdfdrive.com/PDF Drive is your search engine for PDF files. As of today we have 80,137,653 eBooks for you to download for free. No annoying ads, no download limits, enjoy it and don’t forget to bookmark and share the love!

Forskningsmagasinet APOLLON UiO: Universitetet i Oslo. Rikt med temaer:

https://www.apollon.uio.no/tema/

My Chromosome

My Chromosome  What does the term pathology mean? Hva er patologi?

What does the term pathology mean? Hva er patologi?

Patologer er leger som er eksperter med spesialutdannelse i patologi, og er spesialister i å tolke forandringer og abnormaliteter i syke organer, vev og celler. Med dette kan patologene tolke og avgi pasientdiagnoser, ofte kreft/ cancer og forstadier til kreft. De kan si noe om årsaker og prognose, og kan gi råd, forklaringer og terapihjelp til behandlende lege.

https://www.youtube.com/user/ilovepathology/featured

YouTube Video

The Royal College of Pathologists

What is a pathologist?

Pathologists are experts in disease.

Gå også til flere egne lenker – links:They use their expertise to support every aspect of healthcare, from guiding doctors on the right way to treat common diseases,

to treating patients with life-threatening conditions.

Patologene er «legenes lege»

Her også Corona. Klima Climate4you

1 PATOLOGI. Lenke helt fra 1996. Første i Nord-Europa (Nå 26 år) :

https://www.patologi.com eller http://patologi.no

2 SKYPAT Litt nyere patologiside: https://www.skypat.no

3 FINNMEST finn “Finnmest finn alt”: https://www.skypat.no/finnmest

4 TVILER Sannhet Usikkerhet: https://www.skypat.no/tviler

5 SKYPAT wordpress. Mye om klimaet vær: https://www.skypat.no/wordpress

6 PATOLOGI wordpress Mere om bl. a. patologi : https://www.patologi.com/wordpress

Ovarietumor

Ovarietumor  Mammakreft makroskopisk

Mammakreft makroskopisk

Glandula parotis

Glandula parotis

Grått hår Forstadie til kreft

Grått hår Forstadie til kreft

Resultat etter barbering

Resultat etter barbering

Hentet fra det medisinske fakultet, Universitetet i Oslo: Mediearkiv/ Medieserver (videoer medisin mp4)

Mediearkiv for ekstern e-læring: https://www.med.uio.no/studier/ressurser/elaring/mediearkiv/Medieserver/

Fremtidens patologi er digital. Fra Tidsskriftet forfattere: Dordi Lea, Linda Hatleskog https://tidsskriftet.no/2022/06/kronikk/fremtidens-patologi-er-digital

“Interview with a Histopathologist: “One of the medical specialties not everyone knows about”

Two basic points: 1. Not all cancers progress & 2.) Cancer survival statistics can be very misleading. [March 2018 keynote at The United States and Canadian Academy of Pathology in Vancouver, BC]

CANCER NEWS:

MAYO CLINIC CANCER Medical Professionals

Medical Professionals news and the latest information about Cancer.

https://www.mayoclinic.org/medical-professionals/cancer/news

Cancer NEWS/ NIH National Cancer Institute

https://www.cancer.gov/news-events/cancer-currents-blog

TheScientist Exploring Life, Inspiring Innovation

Cancer

https://www.the-scientist.com/tag/cancer

DKTK German Cancer Consortium

https://dktk.dkfz.de/en/about-us/news

Archives of Pathology & Laboratory Medicine https://meridian.allenpress.com/aplm

PathologyOutlines.com find pathology information fast https://www.pathologyoutlines.com/

The Internet Pathology Laboratory for Medical Education (The University of Utah https://webpath.med.utah.edu/

The Best Microscopic Footage Of Nikon’s 2019 Competition

Statens helsetilsyn 2-99 Patologifaget i det norske helsevesen

Søk medisinske artikler: PubMed (National Library of Medicine) https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/

Asclepius Asklepios Eskulap. Gresk gud for medisin og helbredelse.

Asclepius Asklepios Eskulap. Gresk gud for medisin og helbredelse.

Patologi – Pathology – Best nice website

Patologi – Pathology – Best nice website

Kreft og sykelige forandringer

Vitenskap

forskning og fremtid

blogg blog

“Patologi er alt som ikke er normalt”!

Without pathology, there is no medicine!

Pathologie – Norwegen – La Norvège – Zentrum

Diagnostic and Prognosis

Scientific Medicine – Vitenskapelig Medisin – Evidencebased Pathology

2022

Patologene er ekspert på diagnoser

Stiller kreftdiagnosene og mange andre pasientdiagnoser!

Kunnskap for din riktige diagnose, behandling og prognose!

Faglig kompetanse – din sikkerhet som pasient!

Patologi med focus på deg og pasientene!

Patologi før, under og etter behandling!

On the second Wednesday in November, International Pathology Day offers a platform for pathology and laboratory medicine services to address global health challenges.

International Pathology Day:

Wednesday 15th November 2017

Wednesday 14th November 2018

Wednesday 13th November 2019

Wednesday 11th November 2020

Wednesday 10th November 2021

Wednesday 9th November 2022

Wednesday 8th November 2023

Wednesday 13th November 2024

Wednesday 12th November 2025

Den Norske Patologforening (DNP) fylte 100 år 2023, og 17. og 18. november 2023 ble dette feiret på Grand Hotell, Oslo!

Over 150 år med akademisk patologi i Norge!

Emanuel Fredrik Hagbert Winge. 1 ste professor i patologi

20. sept. 1866

https://lokalhistoriewiki.no/index.php?title=Emanuel_Winge&mobileaction=toggle_view_desktop

Emanuel Winge

Emanuel Winge er gravlagt på Vår Frelsers gravlund i Oslo.

Rundt 1860 fant det sted enorme endringer i den medisinske vitenskapen i Europa ved at den tusenårgamle humoralpatologien ble avløst av celluarpatologiens oppfatninger. I sentrum for dette stod den tyske patologen Rudolf Virchow. Allerede i 1851 hadde den senere så sentrale skikkelsen i norsk helsevesen Christian Thorvald Kierulf – som også var en fetter av Winge – studert hos Virchow i Würzburg. Det var Kierulf som var foranledningen til at Winge med offentlig stipend april 1857–mai 1858 studerte patologisk anatomi hos Virchow, anvendt medisinsk kjemi / urinanalyse hos Heller samt klinisk medisin hos Traube og Oppolzer. Det var også Kierulf som tok initiativet til å opprette et patologisk laboratorium på Rikshospitalet og som høsten 1858 fikk utnevnt Winge til prosektor ved dette etter at han noen måneder hadde virket som reservelege ved Rikshospitalets medisinske avdeling.

Det er korrekt å si at Winge var den som først og fremst brakte den nye celluarpatologien hit til landet. De to små laboratorierommene i det gamle Rikshospitalets bakbygning i Grubbegata ble et medisinsk sentrum. Eldre medisinske professorer og overleger kom dit for å høre Winges mening. Flere av byens leger kom dit med problemer som de trodde kunne bli løst kjemisk eller mikroskopisk. Der fikk de vitenskapelig interesserte unge legene sin første utdannelse i mikroskopi av patologiske preparater. Alt lå vel til rette for at Winge skulle kunne danne en medisinsk skole her i Norge, men slik gikk det imidlertid ikke.

Allerede vinteren 1858–1859 var Winge på en ny utenlandsreise, også nå til Berlin hos Virchow, men også til andre universitetsbyer i Europa. Virchow ble i 1859 innbudt av den norske regjeringen til å studere spedalskheten, og Winge ledsaget ham på reiser i Bergenhus og Trondheims stiftamt. Winge ble etter hvert en viktig person i det medisinske fakultetet. Han var fra 1864 og to år framover dets sekretær. Man gjorde seg stor nytte av Winges evner til å klare opp i vanskelige og kontroversielle fakultetssaker i hans mangeårige senere funksjon ved fakultetet.

Som et tegn på at de nye patologiske læresetningene slo igjennom i Norge, ble det opprettet et spesielt professorat for Winge. Han ble 14. september 1866 utnevnt til professor i medisin – spesielt i alminnelig patologi og patologisk anatomi. Andreas Conradi, som var professor i spesiell patologi og terapi samt overlege ved Rikshospitalets medisinske avdeling, ble imidlertid syk. Winge vikarierte for ham. Etter Conradis død ble han 20. februar 1869 utnevnt som dennes etterfølger uten konkurranse i denne enda mer betydningsfulle stillingen.

Winges virksomhet i denne sentrale lærerstillingen er et viktig stykke av den medisinske utviklingen her i landet. Når det kan hevdes at han «ikke dannet skole», beror nok det på at han manglet en særlig evne til å gi vitenskapelige impulser eller ikke oppmuntret sine underordnede til å gjøre selvstendige undersøkelser. Selv fikk heller ikke Winge skrevet så mye og ingen større sammenfattende verker. Hjalmar Heiberg og Emanuel Winge oppdaget i 1869 Den Winge-Heibergske infektiøse endokarditt (sammenhengen mellom betennelse og endokarditt, altså en feil på hjerteklaffen).

Fra 1873 var Winge medlem av redaksjonen for Norsk magasin for lægevidenskaben. Han deltok mye i det naturvitenskapelige og medisinske internasjonale samarbeidet, særlig innen Norden. Under Uppsala Universitets Jubelfest i 1877 ble Winge utnevnt til æresdoktor ved det medisinske fakultetet. Han var fra 1868 medlem av Videnskabs-Selskapet i Christiania. Winge var religiøst innstilt og var formann for Komitéen for Lægemissionen på Madagaskar.

Carl Birger van der Hagen skriver dette om Emanuel Winge i Norsk biografisk leksikon: «[Winges] fremste innsats var å bringe de store nye oppdagelser fra den oppblomstrende patologiske anatomi inn i den praktiske kliniske medisin, og bruke naturvidenskapelige metoder og kjemiske og mikroskopiske observasjoner fremfor den klassiske empiri. For mange årskull medisinske studenter stod [Winge] som en eksponent for den mangesidige, logiske, deduktive diagnostikk. Han tålte ingen „genial” lyndiagnose, og var en streng, men utpreget rettferdig eksaminator. Han fremhevet heller ikke seg selv som allvitende: „Da Winge engang eksaminerede sig selv”, het det ved en „Oktoberfest”, „gav han sig ikke bedre enn 10.”»

Kilder

- van der Hagen, Carl Birger. Winge, Emanuel Fredrik Hagbarth. Norsk biografisk leksikon.

The Norwegian Society of Pathology. 100 års Jubileum i 2023 !

Patologiavdelingen i Tønsberg/ Vestfold fylke ble opprettet i 1981 og her er et 25 års Jubileumshefte:

Les også: Anonyme leger, William Mc. Kee German. Oversatt av Terje Strand, Oslo 1946.

Som JANUShodet fra Vatikanet.

Patologi :

”Ser bakover og fremover i daglig arbeid”

Patologer undersøker f.eks. om det hos pasienten foreligger forstadier til kreft, manifest kreft, type kreft, om den er hurtigvoksende og har spredt seg. Mange av pasientprøvene dreier seg om denne problematikk og antallet stiger pr. år. Diagnosesvarene blir ofte kommentert med forklaringer og råd til den rekvirerende lege. Diagnosen sier noe om sykdomsprognosen og behandlende lege kan så på riktig måte videre undersøke eller behandle pasienten. Patologene dekker et nødvendig behov for behandlende leger og samarbeide med andre leger er derfor viktig.

PATOLOGI : PASIENTBEHANDLING VIA MIKROSKOPET!

Selv om mikroskopering er en gammel teknikk, er tolkningen av mikroskopbildene ofte gullstandard for sykdomsprosessen. Det foreligger enorm informasjon i de mikroskopiske bildene. Som kjent kan man si at hva du ser i verden med dine øyne og også ved hjelp av mikroskop gjelder:

Det foreligger enorm informasjon i de mikroskopiske bildene. Som kjent kan man si at hva du ser i verden med dine øyne og også ved hjelp av mikroskop gjelder:

DET VANSKELIGSTE AV ALT ER Å SE DET SOM LIGGER RETT FORAN ØYNENE DINE!

Was ist das Schwerste von allem? Was dir das Leichteste dünket. Mit den Augen zu sehn, was vor den Augen dir lieget. Quelle: Xenien aus dem Nachlaß 45 (Johann Wolfgang von Goethe).

Det har kommet mange andre sofistikerte medisinske apparater og undersøkelsesmetoder i helsevesenet for å stille pasientdiagnoser for behandling, men en del gir ikke resultater eller tolkningsforhold som er forenlig med den virkelige gullstandard- selv om helsepersonell mener dette. Man kan delvis si:

“A fool with a tool is still a fool”  Dessverre hører ofte en person bare på hva han tror han forstår (Goethe).

Dessverre hører ofte en person bare på hva han tror han forstår (Goethe).

Statestics: Dessverre Mye error/ biasfeil!

“The average human being has 1 breast and 1 testicle”- (Des McHale)

”Thus I learned early on the great importance of a

close correlation between clinical and pathological

studies.

Each complements and supplements the other; it is

impossible to do intelligent surgery without a

thorough understanding of the pathology of disease

and it is equally impossible to make an intelligent

interpretation of pathology without a clear understanding

of its clinical implications.”

Arthur Purdy Stout.

(Bok: ”Guiding The Surgeon `s Hand”, 1997, Editor

Juan Rosai)

Patologi som betyr sykdomslære, er et grunnleggende fag for helsepersonell og er med på å gi “skolemedisinen” vitenskapelig forankring. Faget omhandler sykdommenes årsak, mekanismer, sykdomsutvikling og hvordan de strukturelle og funksjonelle forandringene i organer, vev og celler blir ved de forskjellige sykdommer.

Denne kunnskapen har ført til at lege med patologiutdannelse er spesialist på å tolke forandringer og abnormiteter i syke celler, vev og organer. Arbeidsområdet dreier seg i våre dager altså mest om patologisk anatomi. Forandringene kan være synlig med det blotte øye, men mikroskopisk undersøkelse er helt nødvendig. Patologene prøver å finne ut hva som feiler pasientene og stille de eksakte diagnosene ved sykdommer.

F.eks. får kliniker (lege) og/ eller røntgenlege mistanke om at pasienten har kreft eller legen ønsker å utelukke dette. Lege tar vevs- eller cellemateriale fra pasienten og patologen vurderer og stiller deretter den eksakte diagnose. Dette gjelder også i forbindelse med mammografi for brystkreft og screeningundersøkelse for tykktarmkreft.

The Amazing Microscopic World, Vol 2

Live bl.a. nå og igår.

Live bl.a. nå og igår.

Coronavirus (COVID-19), LIVE i verden. Bl. a. reell oversikt over antall smittede og døde med Korona/ Corona.

https://www.worldometers.info/coronavirus/

Coronavirus VG

Fordelte og satte vaksinedoser i Norge

https://www.vg.no/spesial/corona/vaksinering/norge/#kart

Mye om Coronaviruset i Norge/ Verden VG: https://www.vg.no/spesial/corona/

Aggregation and Prion-Like Properties of Misfolded Tumor Suppressors:

PATHOLOGY OUTLINES.com, find pathology information fast

PATOLOGI OG SKYPAT- for helse, naturvitenskap, realisme og fornuft.

Digital patologi ger kortare väntetider i cancervården. Linköpings Universitetssjukhus, Sverige.

COCHRANE Library. Trusted evidence. Informed decisions. Better health.

? PTLD/ Posttransplant lymphoproliferative disease, noe liknende som funn ved

Diffusion Chamber Cultur fra 1970-80 årenee?

NEWS: Google’s Deep Learning AI project diagnoses cancer faster than pathologists

NEWS: Detecting Cancer Metastases on Gigapixel Pathology Images

Nice LINK: High Quality Pathology Image. Visual Survey of Surgical Pathology

CancerIndex. The Guide to Internet Resources for Cancer family of Web sites, established 1996

Malignes melanom. Universitats Klinicum, Freiburg. 2015.

Pioneers and leaders in microscopy by Dr Rebecca Pool

Pathology of HIV/ AIDS Edward C. Klatt, MD 32nd Edition 2021 PDF: https://webpath.med.utah.edu/AIDS2021.PDF

SkyPat©

SkyPat©

THE POWER OF PATHOLOGY

The Royal College of Pathologist

PATOLOGER ER EKSPERTER PÅ SYKDOMMER.

Mange Videoer/ spillelister/ Kanaler. ( The Royal College of Pathologists is a charity with over 11,000 members worldwide).

https://www.youtube.com/user/ilovepathology/featured

Pathology. Hva er:

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=yYCnwjs1qUs

Cockerell Dermatopathology. (Hudsykdommer) Rikt med vitenskaplige videor.

https://www.youtube.com/channel/UCifzqklb-owNDhm1e5v3uBg/videos

Uscap. Creating a Better Pathologist. Rikt med vitenskaplige videoer.

https://www.youtube.com/channel/UCKghC1egWYr3ct06hqwHE9w/videos

Pathology Riddles. Find pathology troublesome? This channel will try new methods to make pathology learning intriguing and fun.

https://www.youtube.com/channel/UCeNLueaX7VREvVRMHsiHBOA/videos

Dr. Nejib Ben Yahia.Educational videos in surgical anatomic pathology for pathologists and medical students (#pathology, #pathologists) and other subjects in science and life.

https://www.youtube.com/channel/UChAHDXtb6l3r5cnb0GnF8ew/videos

pathCast

https://www.youtube.com/channel/UCRNmhAY99PeW91oCCe9MMpg/videos

PathologyNOW

Dedicated to helping medical students and residents gain a better understanding of Pathology, starting with normal histology. Normal histology videos were created by the University of Rochester Pathology IT Program.

https://www.youtube.com/channel/UCpCgkkQx2T6bVaSh82I5lrA/videos

Pathweb Teacher

Undergraduate and postgraduate pathology videos, including mindmaps, gross and microscopic descriptions.

https://www.youtube.com/channel/UC3FweZwONWAicB72vF9P5ew/videos

Pathology mini tutorials.

https://www.youtube.com/channel/UCeSFXMp6UGR8ryO68v0PcOw/videos

PHILOSOPHIA

De laanske sannheter! Skrevet tirsdag, 19. januar 1999

1. Noe er, og tankene registrerer dette.

2 Tiden består av/ kan bare registreres i form av strukturforandringer .

3. Strukturer er rom/ geografi.

4. Delene i strukturforandringene kan relativt bare fjerne seg eller nærme seg.

5. Det fins små- og stor- sykliske svingninger.

6. Kaoset er også organisert og intet er helt tilfeldig.

7. Alt innvirker mer eller mindre på hverandre.

8. Det eksisterer også ikke- struktur.

9. Alt har sitt rekkefølge.

10. Tiden står ikke stille, men tidsretningen er ukjent og kan ikke bedømmes.

11. Tidsoppfatningen er psykologisk betinget.

12. Hva som skjer kan ikke avgjøres i nuet.

Hva som har skjedd bygger på erindring, data og nok subjektiv tolkning.

Man kan ikke forutsi med sikkerhet nærmeste, videre eller lengere frem i fremtid. Det foreligger sannsynlighet/ prognose eller tro.

Etikk må sees i forhold til kultur, sted og tid.

Alt kan ikke uttrykkes i ord.

Ingen har den samme oppfatning.

Det går ikke an å være alene.

Det som er, er ikke det normale og intet er normalt, men alt relativt.

Det fins bare relativt rettferdighet og intet er egentlig rettferdig.

Samfunnet er ikke klokt.

Alt er ikke mulig og alt kan ikke skje.

Universet starter i den enkelte.

Universet er rundt hvert vesen.

Verden er forskjellig fra individ til individ.

For å se det spesielle, må man avgi fornuften.

Norway 2022

Alt innhold på https://www.skypat.no/pathology er egentlig beregnet til internt bruk av/ for eier. Copyright © SkyPat 1996 – © – Det foreligger ikke ansvar for opphav, innhold o.l. fra eksterne nettsider/ lenker eller sider/ innhold o.l. på https://www.skypat.no/pathology og eiers andre lenker. Bruk utenom av andre personer gjøres på eget ansvar. Vær Varsom- plakatens regler for god presseskikk følges mulig ikke. Enighet i alle linker og sider trenger ikke å være tilstede! All rights reserved.

Mine Lenker:

Overveiende om PATOLOGI:

1.PATOLOGI hovedside, med rik MENU Hovedside i patologi: https://www.skypat.no/pathology

- PATOLOGI wordpress. Mere om bl. a. patologi : https://www.patologi.com/wordpress

- PATOLOGI. Lenke helt fra 1996. Første i Nord-Europa (Nå 26 år) :https://www.patologi.com eller http://patologi.no

- SKYPAT Annen patologiside/ klima: https://www.skypat.no

Overveiene om KLIMA – KLIMAHYSTERI – Fakta:

- SKYPAT wordpress. Mye om klimaet vær: https://www.skypat.no/wordpress

Annet FAKTA:

- FINNMEST finn “Finnmest finn alt”: https://www.skypat.no/finnmest

- TVILER Sannhet Usikkerhet: https://www.skypat.no/tviler

All rights rights reserved Copyright © SkyPat 1996 – © Copyright © SkyPat 1996 Birger Fr. Motzfeldt Laane ![]()

![]()